Hepatitis C is a serious and often-silent liver infection caused by the hepatitis C virus. It is one of five main types of hepatitis (the other four are hepatitis A, B, and the less-common D and E). Hepatitis C is transmitted when an infected person’s blood enters a healthy person’s bloodstream, for example, via contaminated needles (including unsterilized tattoo needles), accidental needlesticks in healthcare workers, and less often, unprotected sex.

Roughly 17,000 new cases occur in the U.S. each year.

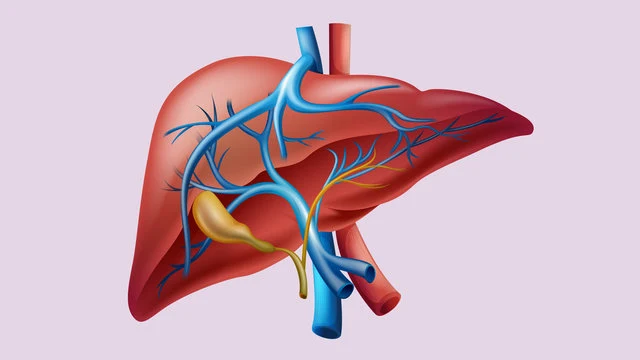

Sometimes hepatitis C is fleeting, in which case the body gets rid of it on its own within a few months of a person’s exposure to the virus. More often, though, the infection quietly lingers, causing the liver to become inflamed. When this happens, severe liver scarring, called cirrhosis, can occur. Chronic hepatitis C may lead to liver cancer, liver failure, and death.

Acute hepatitis C

Acute hepatitis C is a viral infection that develops in the initial weeks or months after the hepatitis C virus (HCV) enters a person’s bloodstream. “Acute” means the illness is sudden and short-lived, occurring within the first two weeks to six months of infection.

In up to 25% of cases, the virus clears the body on its own without treatment.

Although there are treatments for acute hepatitis C, few people experience symptoms to indicate that the infection is present. (For those who do, fever, fatigue, and other flu-like symptoms are common.)

Without obvious signs of illness, most cases of acute hepatitis C lead to chronic infection.

Chronic hepatitis C

An estimated 75% to 85% of people with acute hepatitis C go on to develop chronic infection, lasting at least six months and often much longer. Even at this stage, most people do not experience symptoms. But that doesn’t mean the infection is benign. Years of infection can wreak havoc on the liver, and you may not even know it until problems with liver function begin to surface.

Often, chronic hepatitis C is detected during routine blood testing, or when an infected person tries to donate blood. (Donated blood is routinely tested for hepatitis C, among other infections.)

Some 3 million to 4 million people in the U.S. have chronic hepatitis C, and most are unaware of their condition. Globally, approximately 700,000 people die annually die from liver disease related to hepatitis C.

Signs and symptoms of hepatitis C

Hepatitis C has been called “the silent killer” because the virus often hides in the body for years, escaping detection as it attacks the liver. Since most people don’t have warning signs of hepatitis C (or don’t know how or when they were infected), they don’t seek treatment until many years later. By the time hepatitis C symptoms appear or a diagnosis is made, the damage often is well underway.

If symptoms do appear, they may be mild or severe. Among the most common complaints are:

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Muscle or joint pain

- Poor appetite

- Nausea

- Pain in the upper right part of the abdomen

- Dark yellow urine

- Vomiting

- Yellowish skin or eyes (jaundice)

- Itchy skin

- Pale stools

- Easy bleeding

- Easy bruising

As many as one in four people with chronic hepatitis C go on to develop cirrhosis, or severe scarring of the liver.

These people may have additional symptoms, including swelling of the legs and abdomen, spider-like blood vessels, and a buildup of toxins in the bloodstream that can lead to brain damage.

Chronic hepatitis C is also one of the leading causes of liver cancer, which shares many of the same symptoms as those experienced by people who have had hepatitis C for many years, including fatigue, fever, bloating, right-side pain, and jaundice.

How is hepatitis C diagnosed?

Unless symptoms arise, people with hepatitis C usually don’t know they have the infection until it’s discovered during routine blood testing. If you have symptoms or hepatitis C is suspected, your doctor may press on your abdomen above the liver to see whether the organ is tender or enlarged. Simple blood tests can confirm the diagnosis.

A screening test can tell whether you have developed antibodies to fight off the hepatitis C virus. If you test positive for these antibodies, it means you have been exposed to the virus at some point in your life. The virus may or may not be present.

A second blood test can confirm whether the virus is currently present in your bloodstream. It detects genetic material of the hepatitis C virus, called RNA. If you test positive, it means you have the infection. If not, it means your body cleared the infection on its own.

A third blood test may be ordered to determine the “genotype,” or strain, of the virus. This information may help your doctor select the appropriate treatment.

A liver biopsy may be ordered to check for chronic hepatitis C. This test is performed in a hospital or outpatient facility. A thin biopsy needle is inserted to extract a small sample of liver tissue. You may be given sedatives and pain relief medication.

Hepatitis C treatment

Hepatitis C treatments have vastly improved over the years. Today’s medications are more effective at ridding the body of the virus, and they have fewer side effects.

The type of treatment you receive will depend on the genotype, or strain, of your hepatitis, as well as how much damage your liver has sustained. Other factors, such as previous treatments you’ve received, other health conditions you may have, and whether you are awaiting a liver transplant, may also affect treatment decisions.

Most people in the United States have genotypes 1a or 1b. The next most common genotypes in the U.S. are 2 and 3.

Medications

Some of the newest medicines for hepatitis C genotypes 1, 2, and 3 include: Daclatasvir (Daklinza); Elbasvir/grazoprevir (Zepatier); Ledipasvir (Harvoni); Ombitasvir, paritaprevir, and ritonavir with dasabuvir tablets (Viekira Pak); Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa); Sofosbuvir (Sovaldi); Daclatasvir (Daklinza) with sofosbuvir (Sovaldi); and Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir (Epclusa).

When to see a doctor

See a doctor right away if you think you’ve been in contact with blood from someone who has hepatitis C, or if you have symptoms and suspect you may have been exposed to the virus.

People who are at higher risk for the hepatitis C virus also should be tested. You may be at risk if you:

- Have ever injected an illegal drug.

- Were born from 1945 to 1965. Up to 75% of adults infected with the hepatitis C virus are Baby Boomers. Although the reasons aren't entirely clear, this generation came of age during the 1970s and 1980s, when the rate of new infections was at its peak.

- Received donated blood or organs before 1992, when routine testing for hepatitis C began.

- Have received clotting factor to treat a bleeding disorder, such as hemophilia, before 1987.

- Were born to a mother with hepatitis C.

- Work in health care setting where you are exposed to blood though accidental needlesticks or injury with sharp objects.

- Have had multiple sex partners, a history of sexually transmitted disease, or a sex partner who has chronic hepatitis C.

- Are infected with HIV.

- Have had tattoos or body piercings.

- Are on long-term hemodialysis to filter your blood because your kidneys aren’t functioning properly.

- Have abnormal liver tests or liver disease.

- Work or live in a prison.

- Are a man who has sex with men.

What causes hepatitis C?

The liver infection known as hepatitis C is caused by the hepatitis C virus. It is the most common chronic bloodborne infection in the United States and a major cause of liver disease, including cirrhosis and liver cancer.

The hepatitis C virus is believed to be responsible for 60% to 70% of all types of chronic hepatitis.

You cannot get hepatitis C from food or drink or casual contact with an infected person. It passes from an infected person to a healthy person through blood.

Many infections occur because people share needles, syringes and other equipment to inject drugs. But any activity that exposes a person to the blood of someone with hepatitis C can pose a risk.

Is hepatitis C curable?

Today, hepatitis C is highly treatable. Up to 90% of people can be cured with new antiviral medicines, according to the World Health Organization. These newer-generation medicines work faster and with fewer adverse effects than older treatments.

Someone is considered “cured” when signs of the virus disappear six months after completing a prescribed treatment regimen. People with chronic hepatitis C should talk to a doctor who specializes in the care of hepatitis C patients about specific treatments and whether their hepatitis is curable.

How do you get hepatitis C?

Hepatitis C is a viral infection, but unlike the common cold, you cannot catch or spread it to others by sneezing, coughing, or shaking hands. Instead, it’s contracted though contact with an infected person’s blood.

People who share needles and other paraphernalia used to inject illegal drugs are at high risk of infection. Healthcare workers can get it through needlestick and sharps injuries, and people who get tattoos can get it from unsterilized needles. About 6% of babies born to mothers with hepatitis C contract the virus. Getting a tattoo or body piercing with equipment that isn’t properly sterilized can also put you at risk.

You can catch hepatitis C by having unprotected sex, but the risk is considered to be much lower, especially among monogamous couples. (People who have a sexually transmitted disease or HIV, multiple sex partners, or who engage in rough sexual intercourse are at higher risk.

How is hepatitis C transmitted?

Hepatitis C is contagious, but you can’t spread it to others the same way you would a cold or the flu. It’s transmitted through blood, commonly the result of unsafe injection practices or contaminated needles, needlesticks and blood transfusions (before July 1992).

If you have hepatitis C, the risk of passing it to someone in your household through casual contact is extremely low. But there are steps that people with hepatitis C can take to avoid transmitting the virus:

- Don’t share needles or other drug paraphernalia with other people.

- Don’t donate blood, organs or sperm.

- Don’t have unprotected sex.

- Cover wounds and blisters.

- Use a bleach solution to clean up blood spills on surfaces.

- Wash with soap and water to remove blood from your hands.

- Carefully dispose of bandages, tissues, tampons and other bloody items.

- Don’t share items that may have come in contact with your blood, including toothbrushes, nail clippers, and razors.

- Stop breastfeeding if your nipples are cracked and bleeding. You may resume nursing once your nipples are healed. (Hepatitis C is not transmitted through breast milk.)

Hepatitis C vaccine

Currently, there is no vaccine to prevent hepatitis C. Developing an effective vaccine is tricky, in part because the hepatitis C virus is capable of developing new strains and subtypes.

However, vaccine research continues on two fronts: preventing the infection and treating people who have chronic hepatitis C infection.

Prevention

Until a vaccine is discovered, the best way to protect people from being exposed to the hepatitis C virus is to avoid contact with other people’s blood or open wounds.

Don’t share needles or other items with blood on them. If you use illegal drugs, seek out treatment or find a local needle exchange program for free, sterile needles. Use only properly sterilized needles for body piercings and tattoos. Wear gloves if you are a health care worker who is exposed to other people’s blood. Use condoms if you have multiple sex partners or have rough sex that may cause bleeding. Avoid sex or use a condom when your or your partner is menstruating or when one or both of you have an open genital sore. For elective surgical procedures that may require a blood transfusion, consider donating your own blood prior to the operation.

Source - Health .com